Peri-implant health

Background

Dental implants are an increasingly popular method of replacing lost teeth and their long-term success is well documented. 1-7 However, similar to a natural tooth, plaque-forming bacteria can build up on the base of dental implants, resulting in an inflammation of the surrounding soft- and hard-tissue. Reversible infections limited to the peri-implant mucosa and with no signs of additional bone loss beyond initial physiological bone remodeling are called peri-implant mucositis. Generally, peri-implant mucositis is a precursor to peri-implantitis. Peri-implantitis is a chronic inflammatory condition in the peri-implant connectivity tissue associated with progressive bone loss of supporting bone beyond physiological crestal bone remodeling.

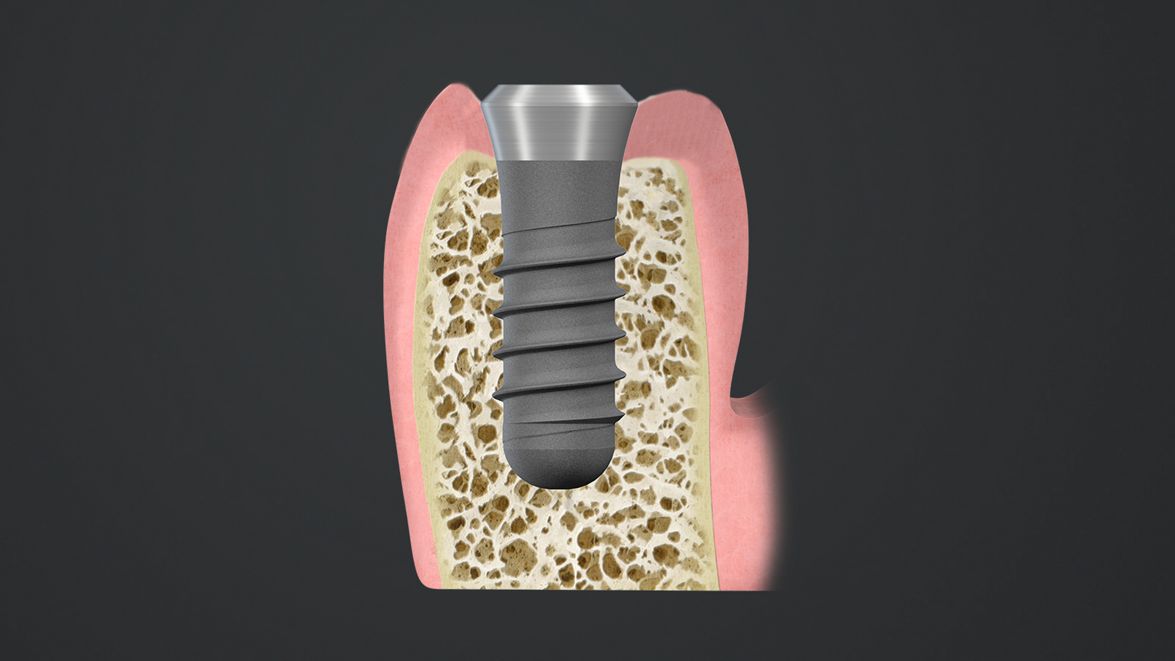

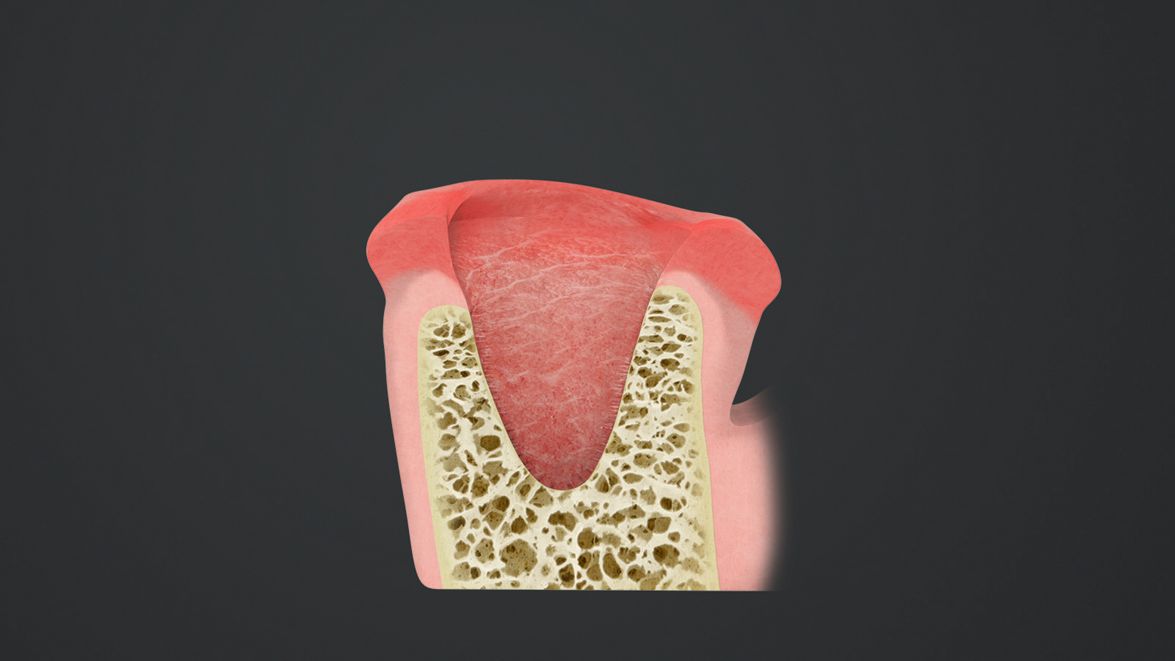

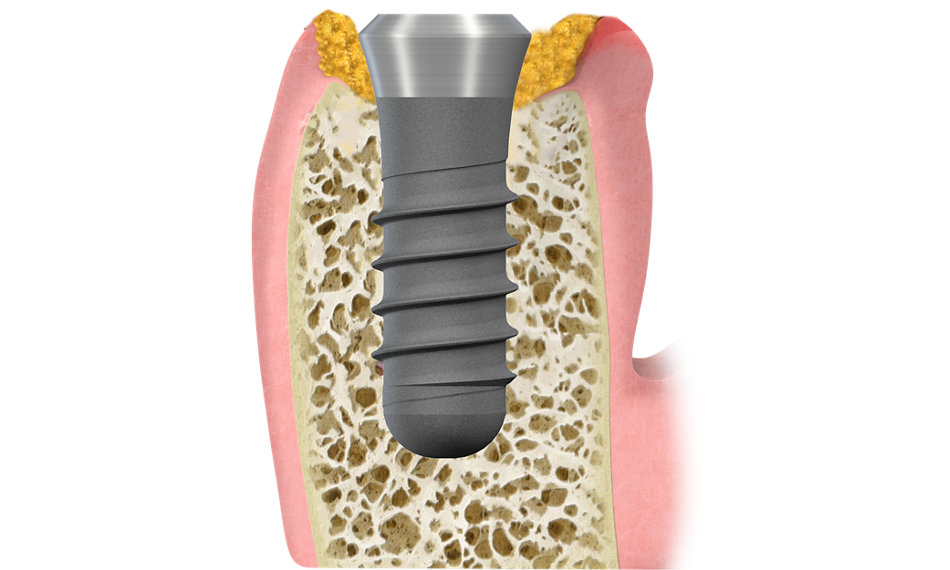

Peri-implant health

Absence of signs of soft tissue inflammation, e.g. absence of bleeding on gentle probing (BoP) and suppuration31 and no bone loss.

(Image courtesy of Prof. Dr. G. E. Salvi)

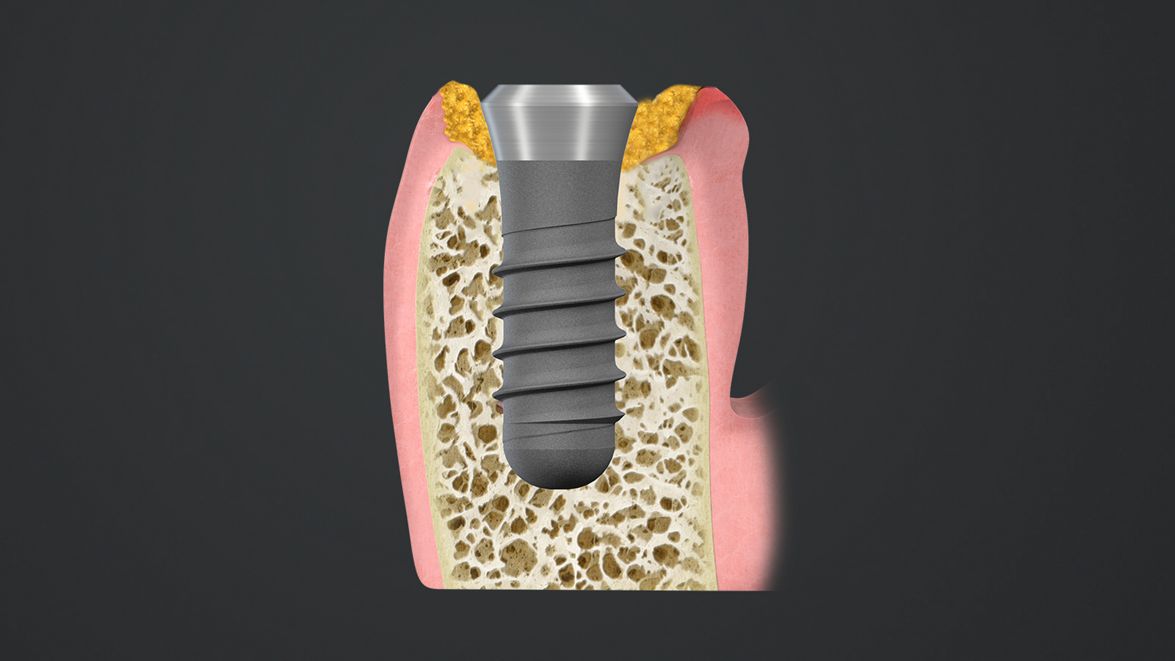

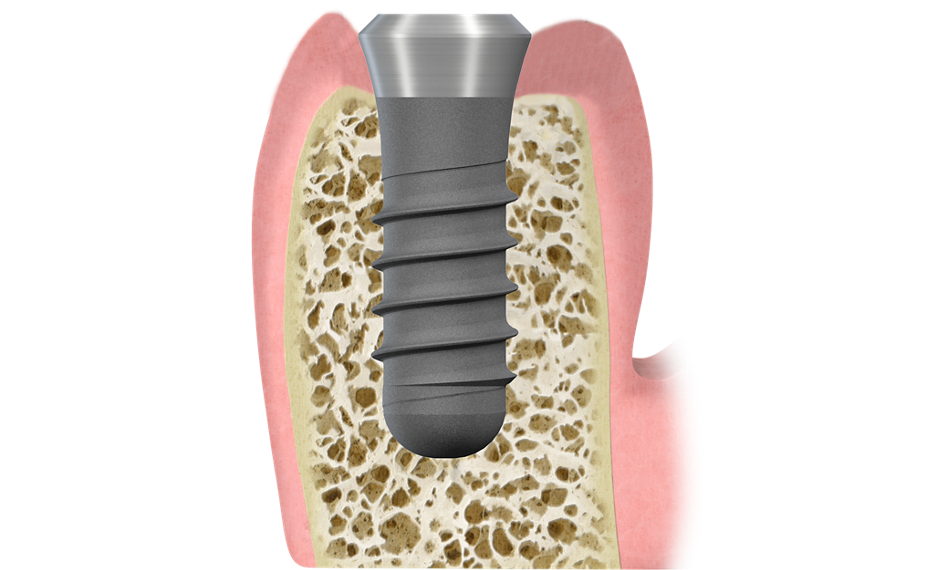

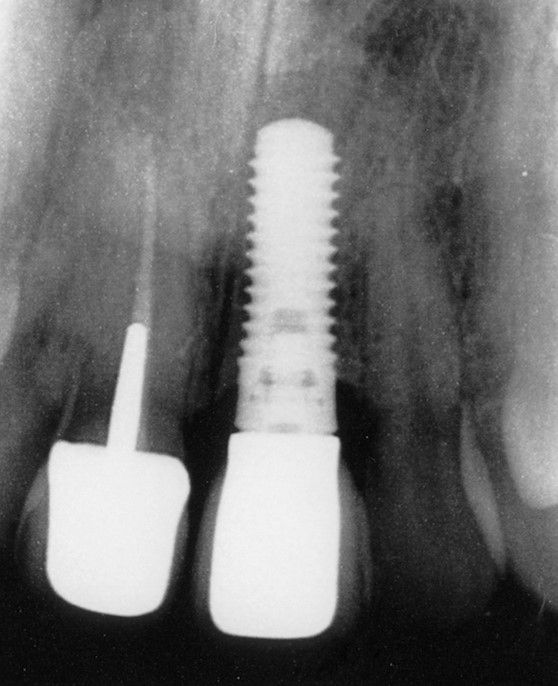

Peri-implant mucositis

Reversible inflammation of the peri-implant mucosa with bleeding on gentle probing and/or suppuration, but without bone loss.8

(Image courtesy of Prof. Dr. G. E. Salvi)

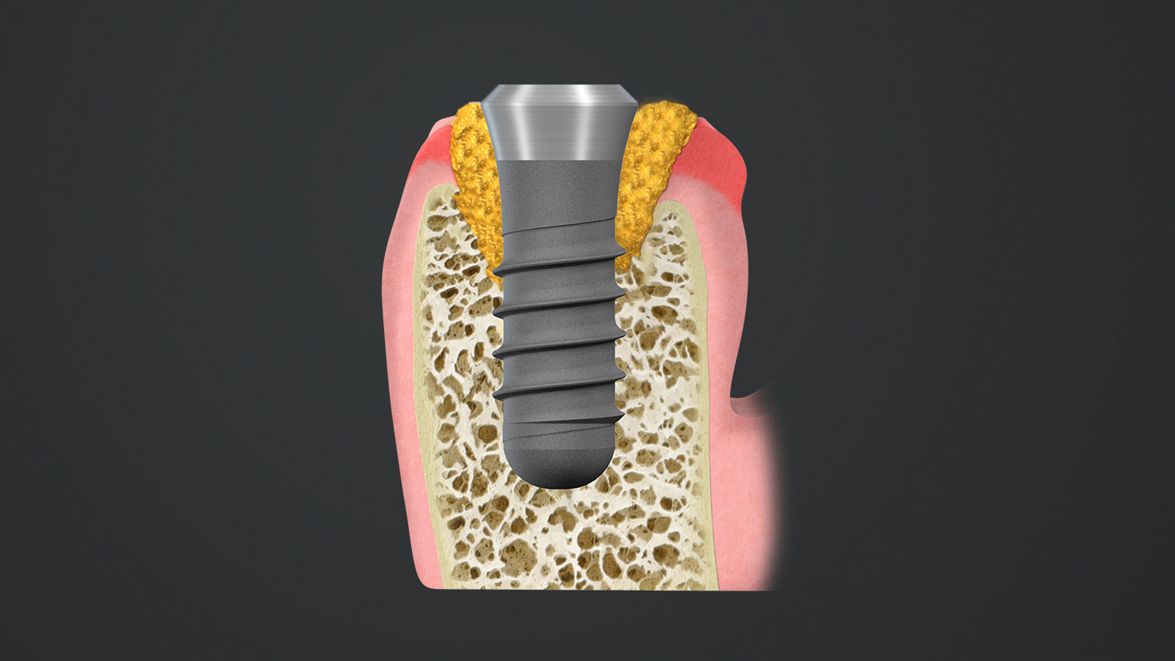

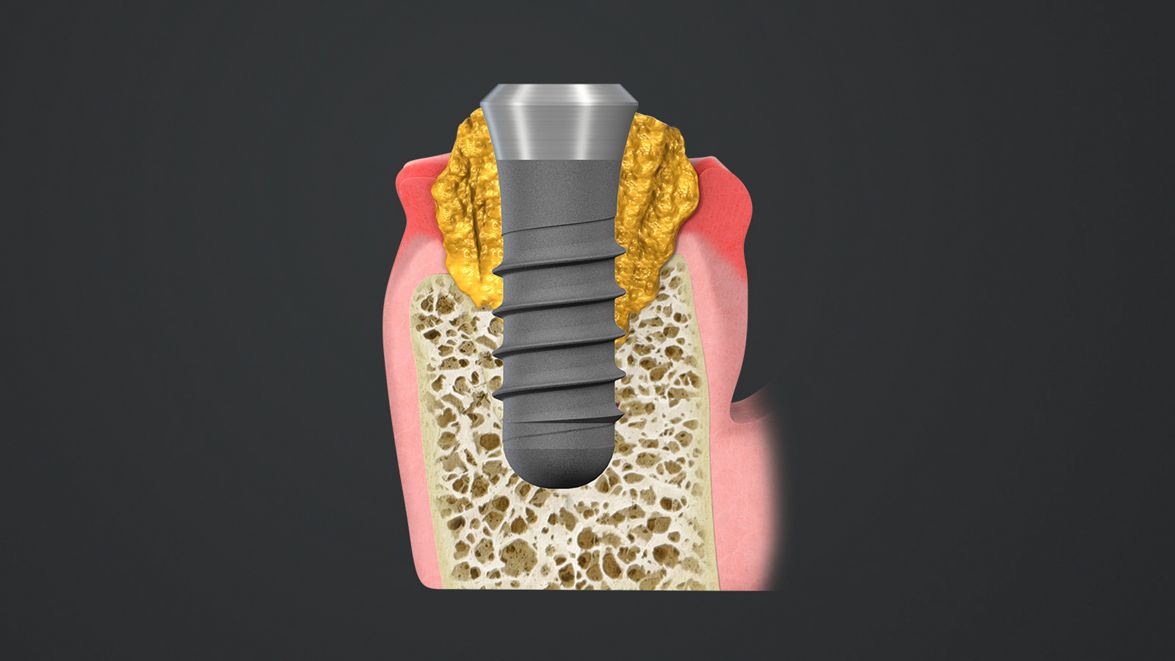

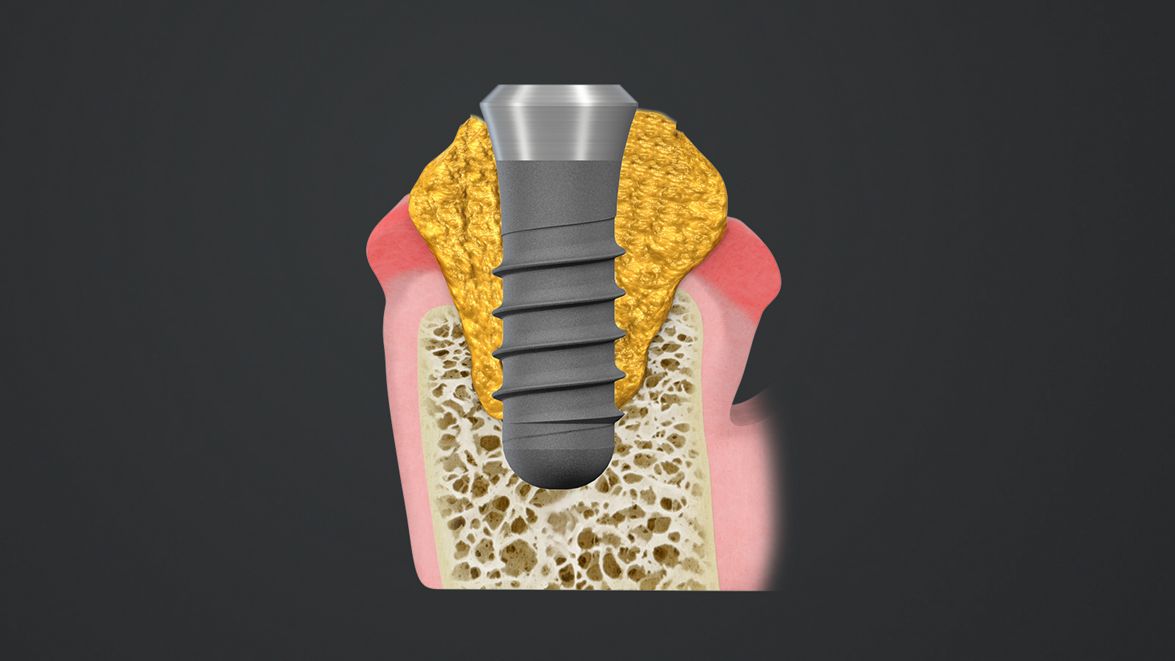

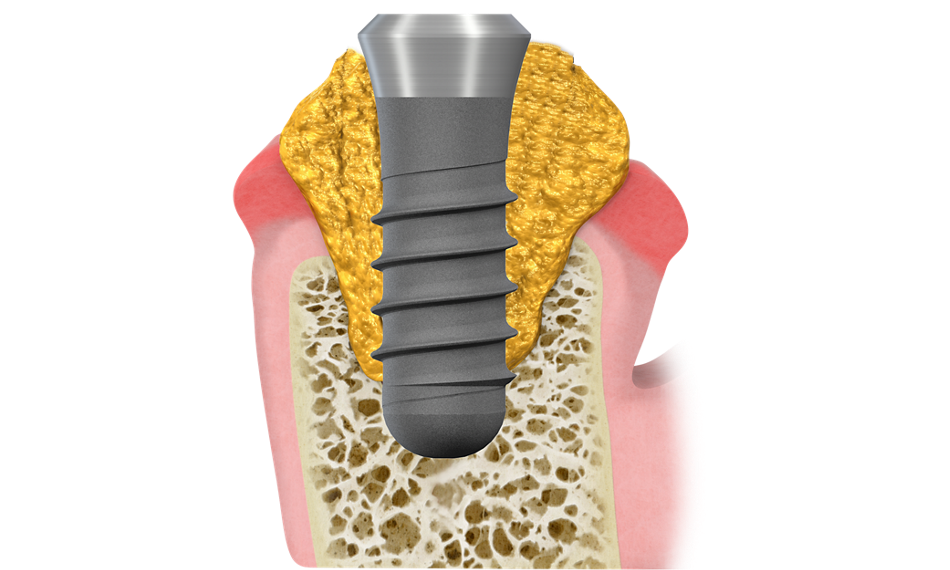

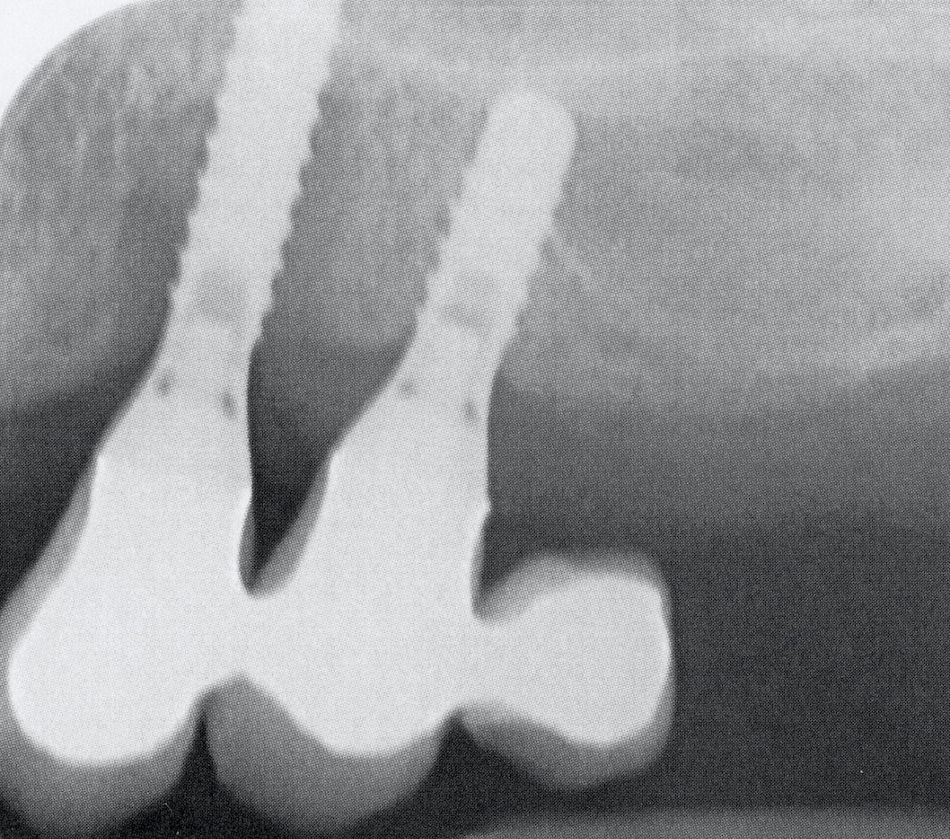

Peri-implantitis

Plaque-associated chronic inflammatory condition with progressive bone loss. 1

(Image courtesy of Prof. Dr. G. E. Salvi)

Prevalence

Reliable statistics depend essentially on a sufficient amount of data gathered following comparable and clearly defined criteria. This is missing in the field of peri-implantitis due to a lack of consensus on terminology, etiology, diagnosis and prognosis.

Therefore, the reported prevalence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis on patient- and implant-level varies widely depending on the study and given case definition, e.g. the threshold defining physiological peri-implant bone loss.

However, most recent systematic reviews and meta-analysis suggests the patient prevalence of peri-implant mucositis to be around 43% (range: 19%-65%) and for peri-implantitis 22% (range: 1%-47%). As not every implant is affected, the reported prevalence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis at the implant level is lower, 30.7% and 12.8% respectively. 9, 10, 11

The latest scientific papers on peri-implantitis classification and prevalence

Risk factors

Accumulation of bacterial biofilms are the main cause for peri-implant complications. Patients with a history of chronic periodontitis have a significantly greater risk of developing a peri-implantitis.

Other potential risk factors are poor patient- and professional-administered oral hygiene and maintenance measures, lack of accessibility of implant sites due to prosthetic reconstruction, smoking, implant system used, systemic diseases (e.g. Diabetes Mellitus, Osteoporosis) presence of submucosal cement, various genetic and iatrogenic factors as well as occlusal overload. 20-26

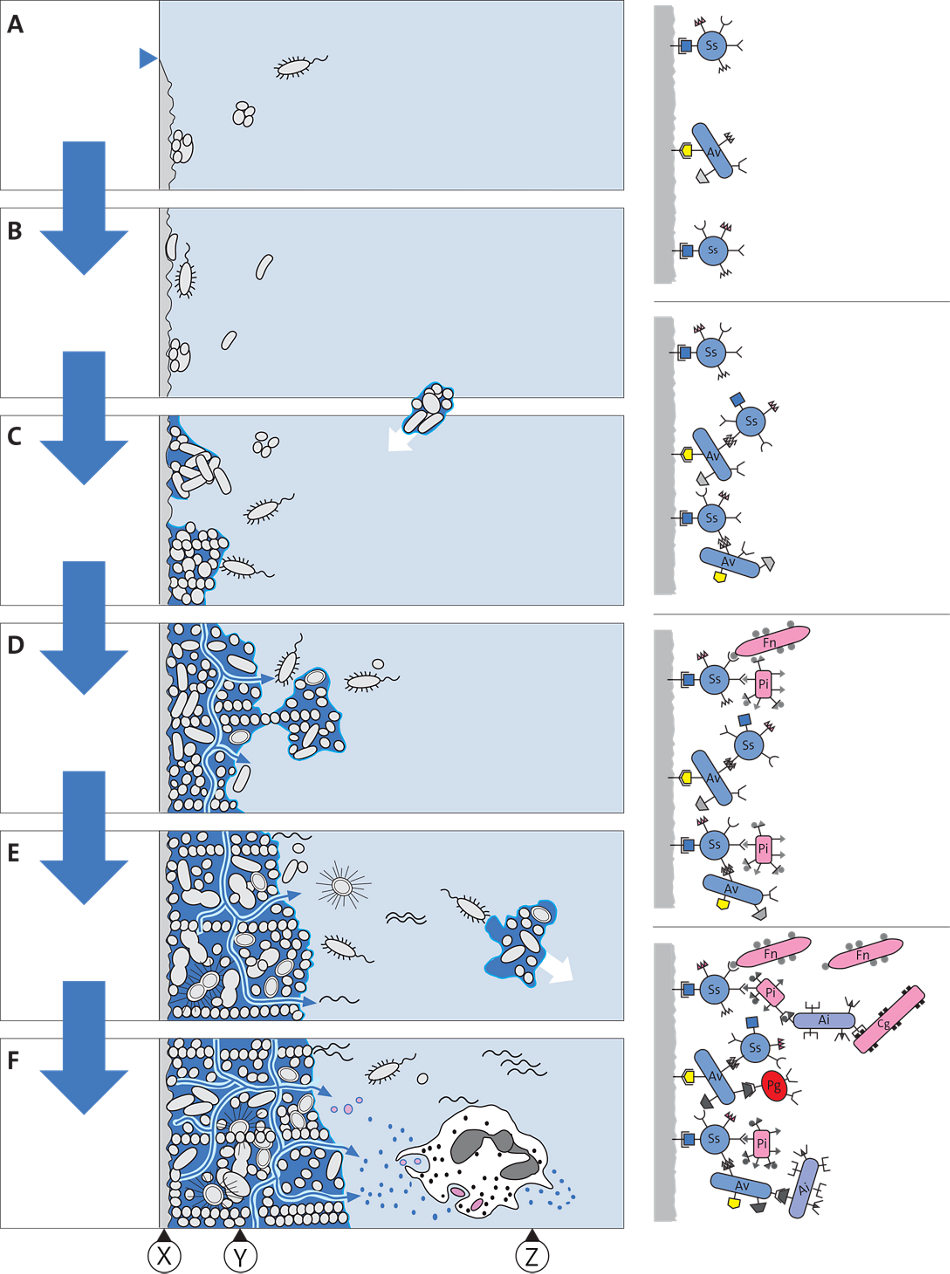

Biofilm

A biofilm is a structured multicellular microbial association with a surface. Oral biofilms consist of various microbial communities in which the resident bacterial cells form mutualistic partnerships.27 The foundations of oral plaque are laid by primary colonizers, planktonic and free-floating microbes that possess special surface molecules (adhesins) that act like a molecular glue, predominantly streptococci, and actinomyces (A, B).

A Association

B Adhesion

C Proliferation

D Microcolonies

E Biofilm formation

F Growth, “maturation”

X Surface

Y Biofilm—“Attached Plaque”

Z Planktonic Phase

Copyright Wolf u. a., Periodontology (ISBN 3131417617) © 2006; Courtesy of Georg Thieme Verlag KG

Subsequently, other microorganisms adhere to the primary colonizers. Adhesion allows the bacteria to resist physical stresses imposed by e.g. fluid movement that could separate the cells from a nutrient source. Bacterial proliferation ensues (C) and as the biofilm grows in complexity, different microenvironments are formed within (D). Throughout the development of a complex biofilm, adherent bacteria sense their neighbors and make appropriate responses. Some of these interactions involve signaling molecules such as protective extracellular polysaccharides (e.g., dextrans, levans). These polysaccharides can provide structure to biofilms and prepare to endure external stresses (E). With maturation the plaque begins to “behave” as a complex organism. Anaerobic organisms increase. Metabolic products and cell wall constituents (e.g., lipopolysaccharides, vesicles) serve to activate the host immune response. Bacteria within the biofilm are now protected from phagocytic cells (PMN) and against exogenous bactericidal agents. In this phase, some bacteria disperse to colonize other surfaces (F).

Prevention

Prevention of peri-implantitis needs to be a combination of serious patient selection, thorough case planning and consistent patient follow-up with regular supportive peri‐implant plaque control.

Ideally, peri-implantitis prevention starts even before placing an implant: an open discussion with the patient, including information about potential risks and the importance of continuous aftercare, is mandatory. A careful weighing of the individual risk factors will then allow for the decision whether an implant is the best solution in that specific patient case. During the case planning, the access for cleaning the future implant site, for individual oral hygiene as well as for professional maintenance care, should always be an important parameter.

After placement of the final prosthetic reconstruction, it is crucial to perform a complete probing and radiographic status of the concerned implant site in order to define a baseline for further observation and follow-up. Periodic monitoring will help to recognize early any deviation from the previously established baseline.

Preventive measures

- Careful and prosthetic-driven case planning

- Regular professional maintenance care after implant therapy

- Instruction for patients on good oral hygiene techniques

- Minimization of modifiable risk factors

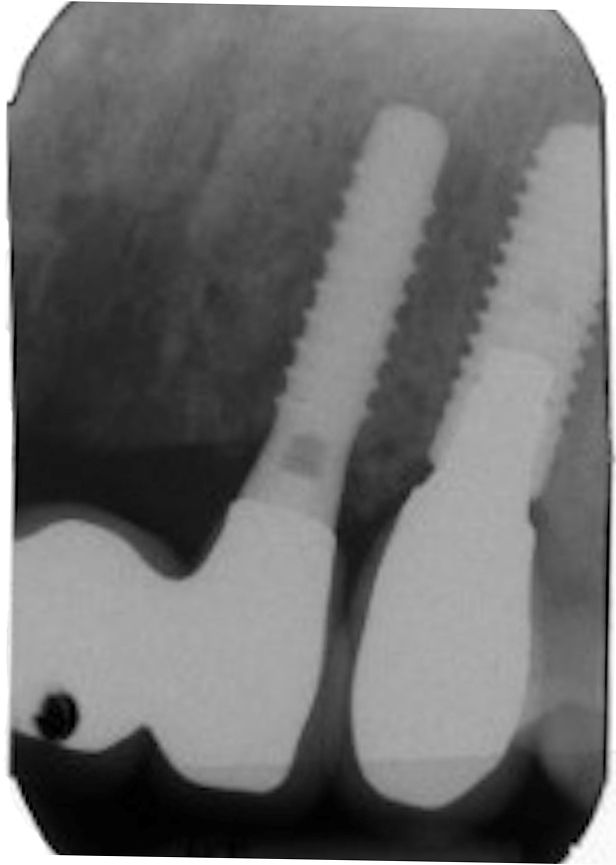

Diagnosis

The main parameters to define peri-implant health status are the progress of probing depth and/or bone loss over time. For this reason, baseline radiographic and probing measurements when the final prosthesis is fixed on an implant and also after a loading period are a prerequisite in order to be able, later on, to correctly judge the peri-implant status of the patient.

Image courtesy of Susan Wingrove RDH, BS.

Diagnosis of peri‐implant health in day‐to‐day clinical practice28-30

- Absence of clinical signs of inflammation.

- Absence of bleeding and/or suppuration on gentle probing.

- No increase in probing depth compared to previous examinations.

- Absence of bone loss beyond crestal bone level changes resulting from initial bone remodeling.

Diagnosis of peri‐implant MUCOSITIS in day‐to‐day clinical practice28-30

- Clinical signs of inflammation.

- Bleeding on gentle probing and/or suppuration.

- Absence of bone loss beyond crestal bone level changes resulting from initial bone remodeling.

Diagnosis of peri‐implantitis in day‐to‐day clinical practice28-30

- Visual inflammatory changes, combined with bleeding and/or suppuration on gentle probing

- Increasing probing depths over time

- Progressive bone loss, compared to radiographic bone level at one year after installation of the final prosthesis and taking into account thresholds exceeding the measurement error (mean 0.5 mm).

- If the chronological evolution of probing depth or bone loss cannot be measured: bone loss of at least 3 mm and/or probing depth of at least 6 mm

Treatment

Maintenance

A comprehensive maintenance protocol is key to ensure the longevity of the implant. Patients with implant-borne restorations (fixed or removable) should be advised to obtain a dental professional examination visit at least every 6 months as a lifelong regimen. Patients at higher risk based on age, ability to perform oral self-care, biological or mechanical complications assessment should be advised to obtain a dental professional examination every 3 months until advised otherwise. A typical professional maintenance visit for patients with dental implants should include an extra-oral and intra-oral health and dental examination, oral hygiene instructions, hygiene instructions for the prostheses and oral hygiene intervention and patient education of foreseeable problems that could impair optimal function of the restoration.

Peri-implant complications can lead to implant loss. But it doesn’t have to be.

Learn more about long-term prevention of peri-implant complications, by Susan Wingrove, RDH, BS